In the last quarter of 2018, in the magazine 'Hommes et Plantes' N ° 107, our article was published dealing with Ginkgos. Here we deliver the original full article, which was then adapted for publication in the CCVS journal.

The tree with forty crowns, forty questions, forty virtues.

By Bénédicte NICOLAS - Les Jardins du Florilège

Ginkgo biloba female from Geebets (Belgium) - Planted in 1753 during the construction of the presbytery

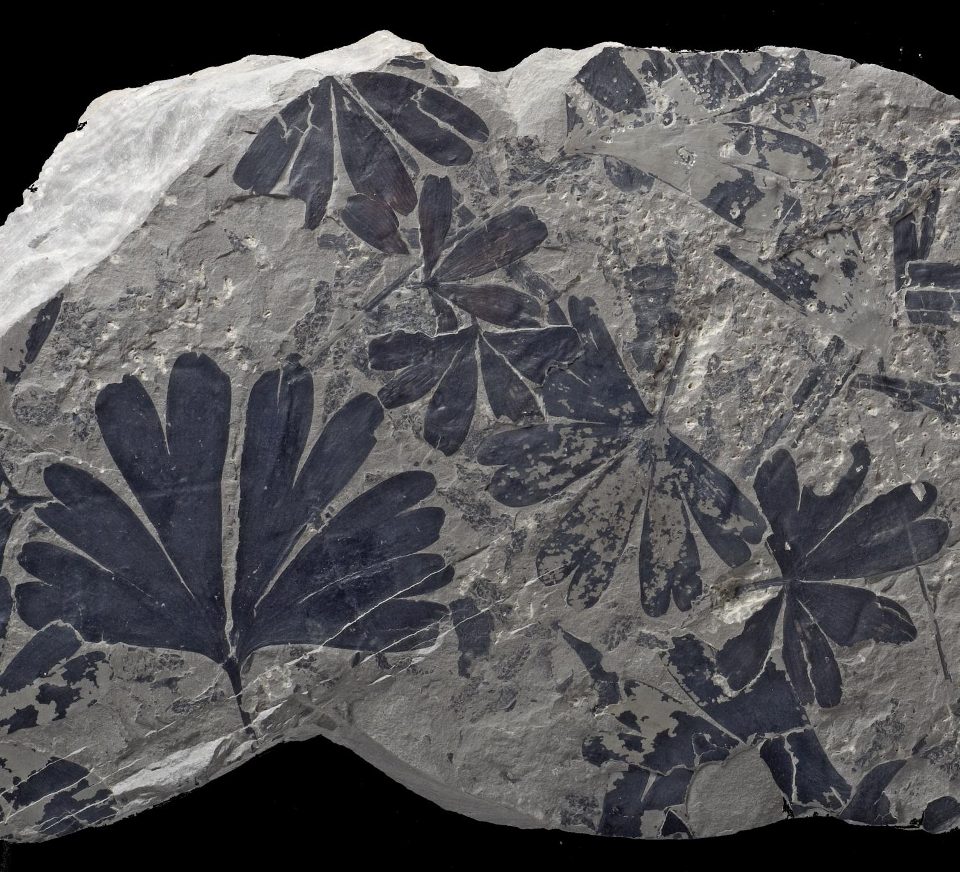

Ginkgo biloba is an ancestral plant. It appears at the time of the dinosaurs, in the Jurassic, 170 million years ago. We know of fossil examples throughout the northern hemisphere.

Currently, there remains a pocket of these living specimens in China, having also resisted the massive fragmentation of land and intensive agriculture that appeared in the 1950s.

In 2012 botanists proved and attested that these subjects are present in the natural state and have never been planted by man.

.jpg)

Ginkgo biloba from the Leiden Arboretum - Hortus botanicus

Planted in 1788 - Male subject with a female graft

Intriguing in more ways than one, Ginkgo seems to be close to conifers. Although its appearance might suggest otherwise since it is not really conical in shape, especially with age, and it bears deciduous leaves, not evergreen needles. However, it is part of the group of gymnosperm anemophilous plants, such as conifers.

Wind-pollinated plants are pollinated by the wind, not by insects, as are entomophilous plants. Gymnosperm plants do not produce flowers or fruit because their reproductive organs appear completely bare.

Zoom on its morphological peculiarities

Generally the Ginkgo has an erect habit, a single trunk that can measure up to 2m in diameter, is branched by strong oblique or horizontal branches. The smaller twigs offer clusters of leaves. It can reach 30m high, under the best conditions.

This plant, close to conifers, has "leaves" rather than needles or scales like the vast majority of its cronies. It is deciduous, a characteristic that is also a minority in this plant group, shared by the Larix, Pseudolarix, Metasequoia and Taxodium.

If we look more closely at its leaves, we find that they are fundamentally different from those of a tree or shrub, or even a perennial. They are not "veined" in the same way.

It is, in reality, a juxtaposition of several needles, glued in a fan, united on the same petiole. So it could well be a conifer with thorns or an "evolved" form. With this device, the Ginkgo performs photosynthesis much better.

Another unique characteristic specific to this plant genus is the formation of "Chi-Chi", taken from Japanese, meaning "udders".

.jpg)

These are drooping growths, similar to aerial roots, formed on the bark of old trunks. They usually appear when the nutrient supply conditions are not sufficient.

The tree increases its bark surface, in order to increase the number of sensors therein and thus recover as much of the substances necessary for its development as possible. "It literally melts and flows its bark, like wax down a candle."

It also adapts its behavior when growing branches. Some return vertically to the soil, to take root there, and pump more water and nutrients the plant needs.

Classification of Ginkgo

Finally, is Ginkgo, yes or no, a conifer?

If we want to be precise and follow the scientific classification meticulously, the answer is no.

If we want to popularize information, and classify this plant among the classic "trees, shrubs, conifers, perennials, climbing plants, ..." the answer could be yes, because it is, indeed, with this class that it has the more in common.

In reality, the Ginkgo is a free electron, the only surviving representative of a class that has almost completely disappeared. Ginkgo is therefore a Ginkgo, and nothing else.

Not all scientific currents are of the same opinion and the classification tables differ from one movement, or one research group, to another. In addition, over the course of discoveries, certainties replace hypotheses, sometimes contradicting them. The task therefore remains difficult.

But let's try to see more clearly and understand why we tend to "store" Ginkgo with conifers.

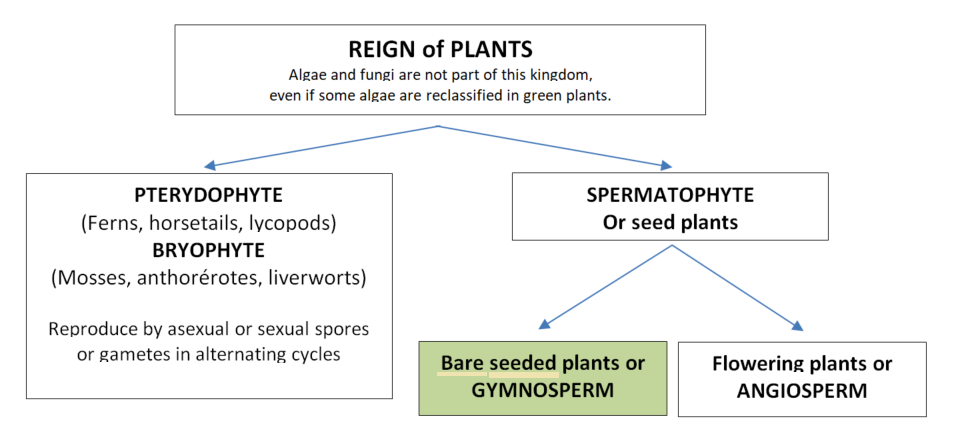

The plant kingdom is subdivided into several orders, classes, etc. The distribution is mainly made on the observation, made by scientists, of the reproductive organs: flowers, fruits, seeds.

Here is a very simplified table that more or less agrees with everyone.

It tries to follow the phylogenetic classification (Established by Willi Hennig, a German biologist, in 1950. It spreads in Europe, over the translations, in the decades that follow, to be mainly recognized today, even if it does still debate).

Ginkgo, indisputably, is one of the Gymnosperms. It does not produce a flower and its reproductive, sexual organs are "bare seeds". Male inflorescences are hanging clusters of open scales containing pollen (like conifers). They dry up and fall off once the pollen is released. The female inflorescences boil down to a biovular petiole.

Conifers are also part of this group, but you could say that the similarity ends here.

Let us dissect this branch of Gymnosperms, by this other table, very simplified, but also heckled.

The different arrow systems (orange, blue or green) show the possible sub-branches, on the basis of separate observations. Sometimes, Ginkgo observes similarities with Cycas, sometimes with conifers. Thus, some botanists prefer to distinguish them completely, since it also has fundamental differences with these other two groups. Our purpose is not to take sides or to point out similarities or differences. What we can say, taking this qualification into account, is that Ginkgo is not a tree, like oak or maple would be. For short, and some will agree with this statement, Ginkgo "is close" to conifers.

To each his gender

Ginkgo is an agame plant, or dioecious. There are therefore two kinds: male or female. In nature, the proportion is 3 females for 2 males.

.jpg)

It is difficult to differentiate males from females, with the naked eye, except by the appearance of the first inflorescences, ie after 20 years.

Among gymnosperm plants, we do not speak of fruit. Here, the female reproductive organ, the ovum, consists of a nucleus, the nucellus, protected by a membrane, or a differentiated protective tissue, the integument. The female inflorescences, for their part, are made up of simple, green, biovulated peduncles that appear in the axils of the leaves. They merge, moreover, very easily with the leaves, when breaking.

Female subjects have the reputation for "smelling bad".

This happens, indeed, for a short time, when the egg falls to the ground, while its integument is breaking down.

It is the butanoic acid, contained in the latter, that is released and gives off this rancid smell. The concern becomes major, mainly with mature subjects, often over 30 years old. Until then, it is quite attractive to be able to enjoy the magnificence of a Ginkgo, male or female, in your garden. If necessary, the complete harvest of ripe eggs will solve the problem and may delight a horticultural producer.

In Japan, it is also called "the tree of the grandfather and the grandson" because the one who plants it never sees it "bear fruit". When planted, it becomes, according to legend, the promise of an immortal line.

Male plants, on the other hand, bear cones, or rather pendulous cylindrical catkins, at the end of short branches, similar to those of other conifer families.

As the first reproductive organs usually appear on mature plants, it is rather uncertain whether to rely on any speech to buy a young male or female plant from a seedling. We must prefer a grafted or cuttings subject, for which it is easy to trace the origin.

An index could however help in the recognition of individuals, but remains unreliable.

The males shed their leaves a fortnight earlier than the females and they are more pyramidal and slender in shape. We could then identify subjects who are nearby, under identical conditions.

Uncommon longevity

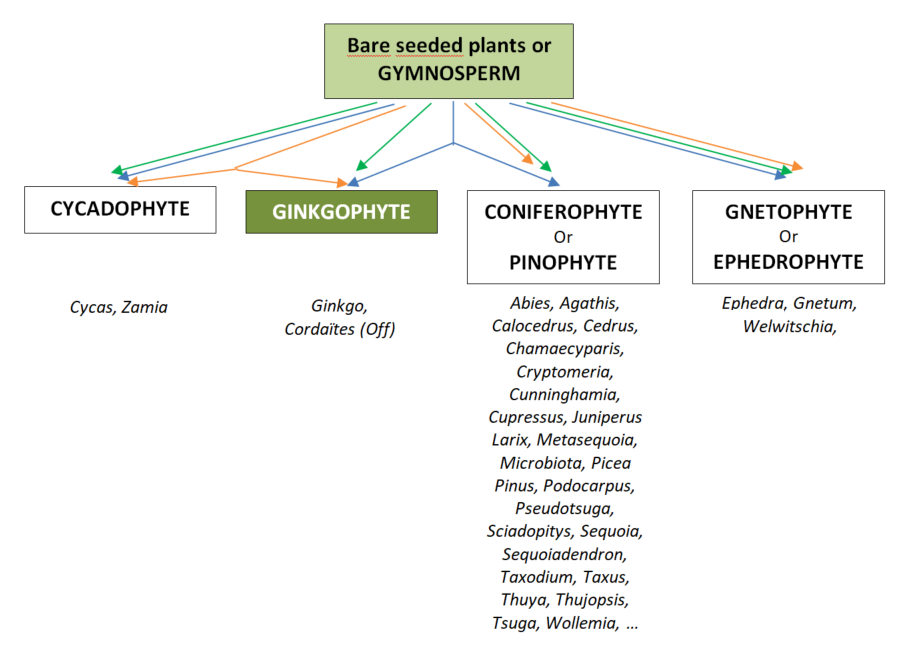

Appeared on earth in the dawn of time, the Ginkgo, today, is a monotypic genus, the only survivor of the Ginkgoaceae family. 270 million years ago, this family was 18 rich. Since then it has shrunk deeply, and only the Ginkgo has come to us.

It is considered, in Europe, as a “living fossil”. For a long time, it was known only in fossil form. It is, perhaps incorrectly, estimated that it has not changed for 51 million years. Jurassic fossils show differences, such as multilobed leaves, while the more recent ones show leaves close to the Ginkgo we know today, with marked two lobes or almost full. However, if we closely study Ginkgo trees from the same seedling, we may find these differences from one subject to another. For example, the 'Landliebe' or 'Mephisto' varieties have multilobed leaves reminiscent of those of the oldest fossils found. These varieties were selected from seedlings.

Photo credit: Stephen McLoughlin Ginkgo biloba 'Landliebe'

.jpg)

Ginkgo biloba Photo credit : Carionmineraux

The primary natural forest where we meet Ginkgos, is located in the Dalou mountains, whose highest point flirts with 2,250m, in the province of Guizhou, in southwest China. The climate is subtropical, hot and humid; limestone soil. It sometimes grows in difficult conditions, even on rock, on the mountainside.

Besides 'Ginkgo biloba', these fragments of primary forest contain beautiful samples of different plants in the wild and original, such as Metasequoia, Liquidambar, Cunninghamia, Cornus, Davidia, Glyptostrobus, Keteleeria, Taiwania, Nyssa, Carya, and many others.

We meet Ginkgo trees from 350 to 900 years old, or even up to 1250 years old, to make the oldest oaks or Sequoiadendron on the planet pale.

Around temples, in China and Japan, it is not uncommon to encounter ancient subjects that are thousands of years old. This is the case at the Gu Guanyin Buddhist Temple in the Zhongnan Mountains of China, where an impressive 1400-year-old Ginkgo tree blooms in the courtyard. It draws crowds from all over the country in autumn with its carpet of gold leaves by the thousand; a Chinese way to celebrate autumn.

In fact, Ginkgo has been planted by monks since the years 1.100 BC. They appreciate it for its beautiful aesthetic and medicinal qualities; but above all, the legends lend it a protective role.

Foolproof resistance

Natural attacks :

In its original forest, the environment is hostile, punctuated by outcropping limestone rocks and subject to recurring earthquakes. It is regularly encountered on the side of a crevasse, growing directly on the rock, exposed to full sun.

When injured, he changes his metabolism in order to survive. This is how he especially develops "chi-chi", aerial roots. These growths are erroneously associated with the age of the tree, but they are not. It is a mode of survival and appears only, possibly, when the subject is put in danger.

It can also develop several trunks, side by side, in order to draw more resources from even very poor soil.

It willingly changes the orientation of its branches or the development of its leaves. It is thus that on the same subject, one meets main branches as well vertical as horizontal, even oblique, or leaves of several types: tubular, atrophied, plane, whole or multilobed.

.jpg)

It suffices to observe the different subjects of Ginkgo biloba 'Pendula’ from the botanical garden of Nancy in France, all from the same selection. They offer very different ports.

.jpg)

.jpg)

It resists better, than any other plant, to fungi, diseases and parasites. Naturally, Ginkgo detects, via numerous sensors, its potentially dangerous unwanted substances, and produces the chemicals necessary to eradicate them. It is by wanting to feed on the leaves or other parts of the plant that the parasites ingest the fatal substances. The signal is given and therefore, very few risk "consuming" Ginkgo.

In addition, Ginkgo knows how to ally itself with effective partners. A French pharmacologist from Tours has discovered that ginkgo leaves are partially covered with an archaic form of algae, which takes over photosynthesis when the very cells of the leaves are destroyed. This process allows the tree to survive, gives it the ability to last until the next season and to form new leaves.

Human attacks :

Le Ginkgo biloba s'adapte à tout, même à la pollution de nos villes modernes, atmosphère dans laquelle il continue à se développer parfaitement, alors que beaucoup d'autres arbres ou arbustes affichent une grise mine.

C'est aussi le premier arbre à reprendre son cycle végétatif, en 1946, après l'explosion nucléaire à Hiroshima ; alors que 337 autres espèces d’arbre n’y résistent pas. Un sujet emblématique est retrouvé parfaitement sein à 1km de l'épicentre, adossé aux ruines d'un temple. Le temple a été reconstruit autour de ce survivant. Des études ont suivi cet événement, démontrant la grande résistance de cette espèce, aux radiations. Les traces de contaminations étant les plus faibles chez le Ginkgo.

Il résiste également très bien au feu. Il sécrète une forme de caoutchouc, qui enveloppe l’entièreté de son écorce, et l’empêche ainsi de brûler. Un temple japonais, a survécu en 1923 à un incendie. Il était protégé par un alignement de Ginkgo qui a arrêté la progression du feu.

Le Ginkgo et ses vertus

5000-year-old traditional Chinese medicine uses it by consuming its roasted or boiled egg nuclei and dried leaves as an infusion. It lends it many virtues deduced from its observed characteristics, such as resistance or longevity.

By extrapolation we give it multiple powers:

- Antioxidant effects (It would slow down the formation of cancer cells and the production of inflammatory molecules),

- It would improve blood circulation (Blood fluidity would reduce the risk of stroke, as well as migraines, since the brain would be better supplied with water),

- It would promote breathing and improve immunity (It would therefore fight asthma),

- It would improve hearing qualities and prevent tinnitus,

- It would improve neuronal connections and therefore memory (it would block the formation of enzymes responsible for Alzheimer's disease).

Even though scientific studies show that its potential is real, isolating and using active substances remains a headache.

In the 20th century, ginkgolides were extracted, in particular from the leaves, to introduce them into pharmaceutical compositions, thus being able to respond to a growing number of pathologies specific to modern man. The real problem is that we are not sure of anything yet. A plant like ginkgo contains more than 10,000 active substances and we are a long way from knowing them, from being able to extract them and even less from using them wisely. To treat oneself with the fruits or the leaves of Ginkgo remains largely empirical and difficult to control.

Extracting ginkgolides is an industrial process, involving many dangerous products such as acetone or ethanol: They are then eliminated before being incorporated into preparations, but still.

It could still be said today, as it was a long time ago, that the strength of the mind is much greater than that of the body. By keeping in mind all the symbolism of the tree, and by absorbing its substances, we will certainly be better off spiritually.

In Europe

Source: soyinfo Center

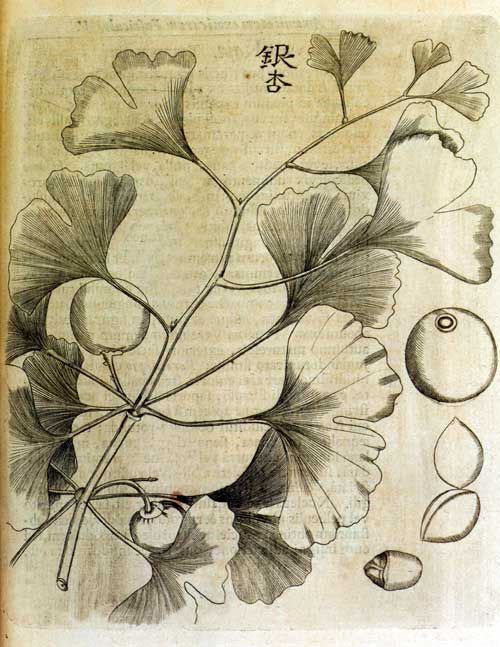

Ginkgo biloba was discovered around 1690 by Englebert Kaempfer, a German botanist, who gives a first scientific description in his book "Amoenitatum exoticarum 'in 1712. He proposes the name Ginkgo on the basis of his Japanese name" Gin Yyo "which means "Duck leg" next to the shape of its leaf.

Kaempfer illustration in « Amoenitatum exoticarum »

The Chinese call it "Yin (silver) Hing (Apricot)" from which one of its French appellations is derived: the silver apricot. It is more commonly known, in french, as the "40 crown tree", the exorbitant amount spent by a wealthy collector in Paris, M. de Pétigny, around 1780, to obtain a jar of five of these subjects. It is also found, by extrapolation, under the name of "tree of a thousand crowns", in reference to the carpet of gold leaf, which can be seen at its foot in autumn.

.jpg)

The "Pagoda tree" is still used to name it.

Buddhist monks planted these revered trees around their temples and pagodas to keep out the fire. In the 19th century, it was called "Japanese walnut".

The first tree was planted in Europe in Utrecht, in the "Oude Hortus", in 1735, from a seedling made in 1927, at the university itself. It appeared in 1754, in England, where it was cultivated at the Gordon School of Botany, and then planted at Kew Garden in 1762.

In 1771, Linnaeus, in his binomial nomenclature, added the genus 'biloba' in reference to its generally and particularly bilobed leaves. This name has been officially recognized since and the exact name is "Ginkgo biloba L.", L. referring to Karl von Linné himself, this eminent Swedish botanist.

The first Ginkgo in France is the one planted in 1788, 3 rue du Carré-du-Roi in Montpellier. It was Antoine Gouan, botanical assistant at the city's academy, who received him from Auguste Broussonnet, a prominent local scientist and politician, based in London. This is a gift from Sir Joseph Banks, a British naturalist who takes part in James Cook's first voyage around the world. Several layers were extracted from this tree in 1795. One was offered to the botanical gardens of Montpellier and another to Paris. These male trees produced their first cones in 1812, which made it possible to determine their genus.

These trees are still alive.

In 1794, England saw its first Ginkgo "bloom" and in 1876 Darwin spoke of them as "living fossils".

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

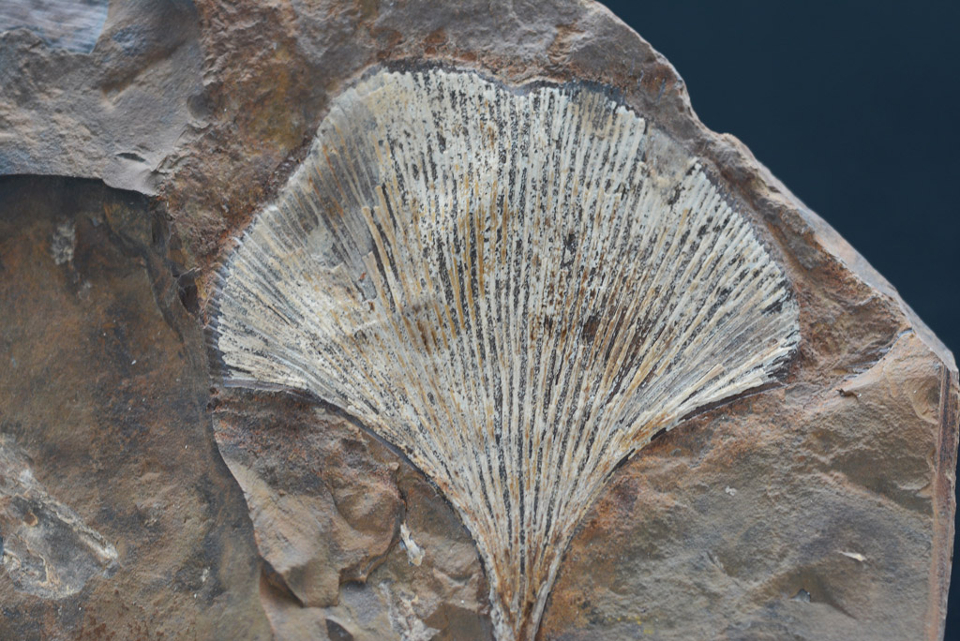

An attempt at a census of the oldest Ginkgos in Europe in the 18th century.

NL-Utrect – De oude Hortus – 1735 – Male <sown in 1727 from Asia (1st Ginkgo in Europe)

B- Geetbets – 37 Dorpsstraat next to the church - 1753 - female <seedlings from Asia - 20.5m

I – Padoue – Botanical Garden of the University of Padua - North gate - 1750 - male with a female branch grafted <seedlings from Asia

D – Weinheim – Schlosspark – 1758 – 20m.

GB- London - Kew Garden – 1762 – Male <sowing in 1754 from Asia

B - Château de Dumon in Tournai – 1766 – 31m

I – Milan – Botanic Garden di Brera – 1775 – 21m

A - Schönbrunn – 1781 - male with a female branch grafted <Foot received from Asia via England

I – Pise – Botanical Garden of Pisa - 1787 - male <seedling from Asia - planted by Giorgio Santi, botanist naturalist.

NL- Leiden – Hortus botanicus – 1788 – male with a female branch grafted

F - Montpellier – 3 rue du carré du roi – 1788 – male <Foot received from Asia via England (GBfr1)

CH - Genève – Bourdigny – 1790 – female <Foot received from Asia via England and France, sent by Thomas Blackie (landscape gardener in charge of Bagatelle castle) GBsu1- presumed dead - not listed on the tree map of Geneva.

F - Montpellier – Jardin des plantes – 1795 – male with a grafted female branch (GBsu1) <GBfr1 layering

F- Paris – jardin des plantes – 1795 – male <GBfr1 layering

Bibliography

Cindy Q. Tang « The Subtropical Vegetation of Southwestern China, Plant Distribution, Diversity and Ecology » , Springer 2015.

Gymnosperm (naked seeds plant) : structure and development par V.P. Singh

the first botanical gardens in geneva - studies in the history of gardens and designed landscapes: sigrist & bungener

Bibliothèque universelle de Genève Nouvelle série, volumes 5 et 6- Bulletin scientifique - Sur l’origine des pieds de Ginkgo femelles qui existent en Europe1836

Defense Mechanisms in Leaves and Fruit of Trees to Fungal Infection - J. E. Adaskaveg